Table of Contents

ToggleWhile working on my term paper about media revolutions and their impact on sports, it became clear that I had to take a deeper dive into sports marketing itself. Understanding how marketing and sports have evolved together is crucial to seeing how the sports industry and different sports ecosystems have been shaped over time. By looking into sports marketing history, we can pinpoint the key moments that changed the landscape, driving sports from a pastime to a global business.

Sports marketing has come a long way—from simple newspaper ads in the 19th century to today’s billion-dollar digital campaigns. The relationship between sports and advertising has been there from the start, growing alongside modern sports themselves. Each era introduced innovations that redefined how brands, teams, and fans connect. Let’s break down the turning points that transformed sports marketing into the powerhouse it is today.

19th Century: Foundations of Sports Marketing in Print

In the 1800s, the seeds of sports marketing were planted through print media and early commercialization of sports. As newspapers became cheap and widespread (the “penny press”), publishers realized sports coverage attracted mass readership – and advertisers. By the late 19th century, big-city newspapers were featuring sports content to boost circulation, even creating dedicated sports departments and sections. The New York World (owned by Joseph Pulitzer) hired the first sports editor in 1883, and William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal introduced the first distinct sports section in 1895 (Moritz, 2017).

This signaled that sports had become mainstream content, giving advertisers a new platform to reach fans. Companies began placing ads around sports news and events, recognizing that the public’s passion for sports could translate into customers.

Sports marketing in this era also took the form of trading cards and endorsements. Starting in the 1870s, American tobacco companies inserted cards featuring popular athletes (especially baseball players) into cigarette packs (Collins, 2024). These early tobacco cards served a dual purpose: reinforcing the packaging and promoting the brand via famous sports figures. Collecting the cards became a hobby, boosting tobacco sales and introducing the concept of using athlete imagery for product marketing.

Sporting goods makers also emerged as pioneers – for example, A.G. Spalding (a former baseball player) founded his sporting goods company in 1876 and soon realized the value of associating his products with teams and athletes (Heffernan, 2023). Spalding sponsored sports tours and supplied equipment to players, effectively using sports celebrity endorsements and events to promote his brand in the late 19th century.

These early efforts marked the genesis of sports marketing: harnessing the popularity of sports heroes and events to sell products.

Impact and Legacy: By 1900, the basic tools of sports marketing – media coverage, athlete endorsements, and event sponsorship – were in place. Newspapers proved that sports could draw eyes for advertisers, a dynamic still seen today with media rights deals and ads during sports broadcasts. Tobacco cards introduced the idea of collectible sports memorabilia as marketing, a tradition that evolved into the trading card industry (and even today’s digital collectibles). Early sponsorship by companies like Spalding set a precedent for the close collaboration between sports and commerce. In short, the 19th century laid the groundwork, turning sports from pure recreation into a vehicle for brand promotion – a foundation upon which future innovations would build.

Timeline: Key 19th-Century Milestones

- 1858: First paid admission to a sporting event – fans pay $0.50 to watch a baseball all-star game, marking the dawn of sports as a commercial entertainment (Thorn, 2018).

- 1870s: Tobacco companies begin inserting sports trading cards (featuring baseball stars) into cigarette packs to spur sales (Collins, 2024).

- 1883: New York World creates the first newspaper sports department (editorial staff devoted to sports) (Moritz, 2017).

- 1895: New York Journal launches the first dedicated sports section in a newspaper, reflecting sports’ huge reader appeal (Moritz, 2017).

- 1880s–1890s: A.G. Spalding and other early sponsors promote sports events (and their products) – early athlete endorsements and branded sporting tours take place (Heffernan, 2023).

Early 20th Century: The Dawn of Sports Endorsements and Sponsorships (1900s–1930s)

The early 20th century saw sports marketing truly take shape through formal endorsements, event sponsorships, and the birth of new advertising mediums. Companies began striking direct deals with athletes and sporting events, anticipating the massive audiences these heroes and contests commanded.

One early landmark was golfer Gene Sarazen’s 1923 contract with Wilson Sporting Goods, often cited as the first major athlete endorsement deal. Sarazen’s deal – which lasted a record 75 years – paid him to use and promote Wilson equipment (Wikipedia contributors, 2025a). This showed companies the long-term value of aligning with a star athlete, and it showed athletes they could earn income beyond competition. By the 1930s, star athletes like Babe Ruth were lending their names to products from candy bars to cereal, validating the power of endorsements in reaching fans.

Sports events themselves also attracted corporate sponsors in this era. Notably, Coca-Cola became the first company to sponsor the Olympic Games in 1928, supplying drinks in Amsterdam and kicking off a relationship that continues to this day (Heffernan, 2023). This was a pivotal shift: a global brand saw the Olympics’ worldwide audience as an opportunity to gain exposure and goodwill, setting a precedent for corporate sponsorship of major sporting events.

Likewise, early professional leagues and teams welcomed sponsors: for example, sporting goods firms provided gear to teams for publicity, and automobile and tobacco companies sponsored trophy cups and racing events. These sponsorships began tying brand identities to sports victories and pageantry.

Another huge development was the rise of radio and broadcast advertising for sports. By the 1920s, live sports were entering American living rooms via radio. The first sports radio broadcasts (such as a 1921 prizefight and baseball game) allowed advertisers to reach fans far from the stadium. Companies like Wheaties cereal quickly capitalized on radio’s reach – in 1926 Wheaties aired one of the first singing radio jingles during a baseball broadcast, boosting its sales. Mass media was amplifying sports marketing potential. This culminated in the first televised sports events in 1939, when NBC experimentally broadcast a college baseball game on May 17, 1939 (Carruthers, n.d.).

Later that year, the first NFL game was televised to a few thousand TV sets. While only a tiny audience saw those early TV games, it foreshadowed the enormous role television would play in sports advertising in coming decades.

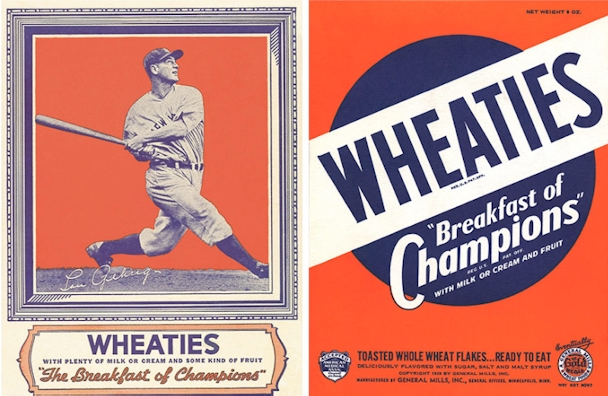

During this time, one of the most iconic sports marketing strategies emerged on a cereal box. In 1934, General Mills began the “Wheaties Breakfast of Champions” campaign, featuring athletes on its cereal packaging (Kindy, 2021). Yankees great Lou Gehrig became the first athlete on a Wheaties box in 1934, appearing on the back. The cereal’s marketing explicitly tied athletic success to the product, with the now-famous slogan positioning Wheaties as the fuel of winners.

This concept – selling a lifestyle or aspiration by linking a product with sports heroes – had a lasting impact, as countless brands since have sought to borrow the prestige of champions. By the 1950s, Wheaties was putting athletes on the front of the box and had firmly ingrained itself in sports culture (Carruthers, n.d.).

Another breakthrough in the 1930s was one of the earliest instances of direct sports sponsorship for product promotion: Adidas’s founder Adi Dassler supplying footwear to Jesse Owens. At the 1936 Berlin Olympics, Owens wore track shoes given by Dassler. Despite the tense atmosphere (Nazi Germany), Owens won four gold medals in Dassler’s shoes. Dassler’s gamble – providing free gear to a star athlete in exchange for exposure – paid off brilliantly. It marked one of the first-known cases of an athlete receiving free merchandise for PR purposes (Carruthers, n.d.).

As a result, Adidas gained international publicity. This pioneering move by Dassler in 1936 essentially birthed the concept of the athlete sponsorship deal, where companies outfit athletes to promote their brand. The practice quickly caught on: by the post-war years, many shoe and apparel companies were competing to have top athletes wear their products.

By the end of the 1930s, all the pieces of modern sports marketing were in play – media broadcasts, endorsements, and corporate sponsorships. Each success built upon the previous innovations: advertisers saw how fans’ emotional connection to sports could drive purchasing decisions, and they refined these techniques for greater effect.

Impact and Legacy: The 1900s–30s era established the viability of sports endorsements and event sponsorships. Athletes became brand ambassadors – a model that would explode in later decades (e.g. Michael Jordan, Tiger Woods) – and sports events became showcases for sponsors (as they are now with ubiquitous signage and “official partners”). The introduction of broadcast media (radio then TV) extended sports marketing’s reach nationally and eventually globally, setting the stage for the big-money media rights and commercials of the late 20th century. In short, this era took sports marketing from ad-hoc experiments to a more organized strategy, demonstrating that investing in sports could yield substantial returns for brands.

Timeline: Key 1900s–1930s Milestones

- 1912: Fenway Park opens in Boston as the first modern MLB stadium – heralding the start of in-stadium advertising (billboards visible in the park) and venue branding opportunities (Carruthers, n.d.).

- 1923: Golfer Gene Sarazen signs a contract with Wilson Sporting Goods – the first long-term athlete endorsement deal on record, spanning 1923–1999 (Wikipedia contributors, 2025a). This proves athletes can successfully promote products for decades.

- 1925: Goodyear’s Pilgrim blimp debuts, flying over the World Series – the first use of a blimp for sports advertising (Carruthers, n.d.). The blimp gives advertisers a highly visible platform above packed stadiums.

- 1928: Coca-Cola sponsors the Amsterdam Olympics – first corporate sponsor of the Olympic Games (Heffernan, 2023). This partnership sets a model for global event sponsorship that continues with the Olympics and World Cup today.

- 1934: Wheaties launches its “Breakfast of Champions” boxes featuring star athletes like Lou Gehrig(Carruthers, n.d.). It’s an early example of a brand using athlete imagery and slogans to associate itself with sports excellence.

- 1936: Adi Dassler (Adidas) gives Jesse Owens free track shoes at the Berlin Olympics – one of the first proactive athlete sponsorships for product exposure (Carruthers, n.d.). Owens’ triumphs highlight the shoes and boost the Adidas brand.

- 1939: First televised sports game in the U.S. (a college baseball game on NBC) airs, followed months later by the first NFL TV broadcast (Carruthers, n.d.). These experiments inaugurate the age of sports on television, hinting at the marketing bonanza to come.

Post-War Era (1940s–1950s): Television Era Begins

In the 1940s and 1950s, sports marketing entered a new phase powered by post-war optimism, new leagues, and, most importantly, the explosion of television. After World War II, sports boomed in popularity as both live entertainment and broadcast content. Television ownership in households skyrocketed in the ’50s, and sports were among the first programs to galvanize national audiences. This created unprecedented advertising opportunities: companies could now reach millions simultaneously during live sports broadcasts, a scale far beyond print or radio.

One early illustration of TV’s impact was the first live coast-to-coast sports telecast in 1951 (an NBC college football game). By the early 1950s, championship games in baseball, football, and college sports were televised, and advertisers eagerly bought sponsorships for these broadcasts. Gillette, for example, sponsored boxing title fights on TV (building on its successful radio sponsorships), using the tagline “Look sharp! Feel sharp!” to sell razors to sports fans. These telecasts forged the template of TV sports sponsorships that still exists – a title sponsor presenting the game, commercial breaks for ads, and brands woven into the event’s identity. Sports had truly moved “into the living rooms of millions”, amplifying the scale of sports marketing (Heffernan, 2023).

Perhaps the most significant development was the debut of regular sports programming on TV and the resulting ad revenue streams. In 1946, the All-America Football Conference (a rival to the NFL) was created partly with television in mind, and by 1955 the NFL had negotiated national TV deals. In baseball, the first World Series to be televised was 1947; advertisers paid then-astonishing fees to reach the growing TV audience. This era also saw companies begin sponsoring teams and leagues, not just events. For instance, in 1950 the English FA Cup (soccer) got a long-term presenting sponsor (though U.S. sports leagues were cautious about overt sponsorship on team uniforms or names until much later).

Crucially, the 1950s introduced sports marketing in venues and team identities. In 1954, the St. Louis Cardinals’ owner made a groundbreaking move by selling naming rights to their ballpark. Sportsman’s Park was renamed Busch Stadium after the brewery Anheuser-Busch.

This was the first sale of stadium naming rights in pro sports. While some fans balked at the commercialization, it opened a new revenue stream and marketing opportunity that many others would soon copy. Owners recognized that the very name of a stadium could be an advertisement – a concept that exploded in later decades (leading to today’s Crypto.com Arenas and AT&T Stadiums). The Busch Stadium deal demonstrated how deeply corporate branding could integrate with sports heritage.

Female athletes and new audiences also emerged as a marketing consideration in the 1940s. During WWII, with many male athletes in service, women’s sports briefly took the spotlight. Philip Wrigley (owner of the Chicago Cubs) founded the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League in 1943 as both a morale booster and a way to keep baseball in the public eye.

The league was marketed heavily (as seen in later depictions like A League of Their Own), with promotions to draw families and showcase female talent. For over a decade the AAGPBL proved that women’s sports could attract crowds – but after the war, it struggled for attention and folded by 1954, in part because marketing support shifted back to male leagues.

The AAGPBL’s rise and fall underscored the importance of sustained marketing: without it, even pioneering sports ventures can fade. (It would take decades before women’s professional leagues returned and garnered serious marketing, a cause still evolving today.)

By the late 1950s, sports marketing was entering a more sophisticated, professional era. Recognizing the growing money in endorsements and media, a young lawyer named Mark McCormack founded IMG (International Management Group) in 1960 after a handshake deal to represent golfer Arnold Palmer. McCormack essentially invented the sports agent industry, proving that athletes could have full-time representation to maximize their branding and earnings (The McCormack Legacy : Isenberg School of Management : UMASS Amherst, n.d.).

Under McCormack, IMG pioneered athlete marketing and negotiated endorsement contracts, TV rights, and appearances, changing sports business forever. This professionalization meant that by the 1960s, sports marketing was no longer just clever ideas by advertisers – it had become an industry in itself.

Impact and Legacy: The post-war period firmly established television as the engine of sports marketing, a role it still holds even in the age of internet streaming. TV turned local stars into national icons and made live sports a shared cultural experience, which advertisers were willing to pay handsomely to be part of. The innovations of the 1940s–50s – stadium naming rights, women’s league marketing, and the rise of dedicated sports marketing firms – all had lasting effects. Stadium naming rights are now common across sports, often netting teams tens of millions annually.

The brief success of the women’s league prefigured later efforts to promote women’s sports (like the WNBA founded in 1996) and showed that marketing investment is key to viability. And Mark McCormack’s vision led to today’s world where top athletes have agents, endorsement portfolios, and brands of their own. By 1960, sports marketing had grown from a part-time pursuit into a full-fledged profession, ready for the big boom of the late 20th century.

Timeline: Key 1940s–1950s Milestones

- 1943: All-American Girls Professional Baseball League debuts, using heavy marketing to draw fans during WWII (Carruthers, n.d.). (The league lasts until 1954, then dissolves as men’s leagues regain focus.)

- 1947: First World Series televised (New York Yankees vs. Brooklyn Dodgers) – advertisers like Gillette sponsor the broadcast, marking the start of TV baseball marketing.

- 1949: Track and golf star Babe Didrikson Zaharias secures a $100,000/yr endorsement deal with Wilson Sporting Goods, the first major endorsement for a female athlete. By the early 1950s she earns about $100k annually from tournaments and endorsements, proving women athletes can be marketable sports celebrities. (Biography: Mildred “Babe” Didrikson Zaharias, n.d.)

- 1951: NBC carries the first live coast-to-coast sports broadcast (college football), demonstrating TV’s ability to connect sports fans nationwide.

- 1954: Sports Illustrated magazine launches, indicating the growing market for sports media and sponsored content (Collins, 2024). (The magazine itself would become famous for its ads and the marketing power of its covers).

- 1954: Anheuser-Busch buys naming rights to Busch Stadium – first corporate-named pro sports venue(Carruthers, n.d.). This legitimizes the idea that even iconic sports venues can double as advertisements.

- 1956: Bowler Don Carter signs a $1 million endorsement contract with Ebonite bowling balls – the largest sports endorsement to date, and the first time any athlete inked a million-dollar deal (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1998). This milestone showed the escalating financial value of athlete marketing.

1960s–1970s: Sports Marketing Matures – Big Endorsements and Broadcasts

By the 1960s and 1970s, sports marketing was hitting its stride as a big business. The convergence of expanding television coverage, the rise of superstar athletes, and innovative marketing strategies made this period a golden age that set many modern precedents. Key developments in this era include the birth of sports marketing agencies, the negotiation of lucrative broadcast deals, the first mega-endorsement contracts, and the packaging of sports as prime-time entertainment.

One of the defining deals of the 1960s actually happened off the field: the formal creation of sports marketing agencies and league-wide sponsorship programs. We’ve noted Mark McCormack founding IMG in 1960 to represent athletes; around the same time, sports entrepreneur Horst Dassler (of Adidas) was pioneering global sports sponsorship. In the 1970s, Horst Dassler partnered with British marketer Patrick Nally to form one of the first firms that sold international sponsorships and TV rights for events.

They convinced FIFA’s president João Havelange that the soccer World Cup could make far more money through corporate sponsors. In a landmark deal, they signed Coca-Cola as FIFA’s first exclusive worldwide sponsor in the mid-1970s for $8 million.

This was revolutionary – it essentially invented the modern global sponsorship model where a few big brands pay top dollar to be official partners. The success of that deal led to others (McDonald’s, etc.) and was soon emulated by the International Olympic Committee. By 1985, the IOC created The Olympic Partners (TOP) program, capping the number of sponsors and charging hefty fees for official status. All this stemmed from the 60s–70s realization that sports leagues could bundle rights and sell packages to sponsors on a scale never done before. It transformed sports marketing from local ad-hoc deals to multi-million-dollar global contracts.

Television, of course, grew even more powerful. The late 1960s brought color TV and satellite broadcasts, meaning events like the Olympics or World Cup could be watched live worldwide, opening new avenues for advertising reach. In the United States, one of the most influential innovations was ABC’s debut of “Monday Night Football” in 1970. For the first time, the NFL was put in a prime-time weeknight slot with a carnival-like broadcast featuring celebrity commentators (Howard Cosell et al.) and flashy production.

This proved a game-changer. Monday Night Football became a cultural institution, attracting huge ratings and drawing non-traditional football viewers with its entertainment value. As one media critic noted, the decision to put NFL games in prime time “altered the sports landscape” and made it a ritual that combined sports and showbiz (Sports Business Journal, 2005).

The broadcast innovations – multiple cameras, instant replay, dramatic narration – not only enhanced viewer engagement but also benefited advertisers with more engaged audiences. Companies flocked to buy ad slots on Monday nights, knowing millions of Americans were tuned in. This era showed that sports on TV could be packaged as entertainment spectaculars, a concept that foreshadowed today’s flashy Super Bowl halftime shows and night games with concert-like productions.

Speaking of the Super Bowl, the late 60s gave birth to it (the first Super Bowl was played in January 1967). By the 1970s, the Super Bowl was becoming the most-watched event in America each year. Advertisers took notice and rates climbed steadily. In 1967, a 30-second Super Bowl TV spot cost around $37,500-$42,500 (Su & McDowell, 2020).

By the mid-1970s it was well into six figures, and rising demand set the stage for the Super Bowl to become an advertising showcase in the 1980s. This period also saw one of the most famous sports commercials of all time air: in 1979, Coca-Cola’s “Hey Kid, Catch!” ad featuring NFL star “Mean” Joe Greene debuted (during Super Bowl XIV in January 1980).

That heartwarming commercial, in which a young fan gives a weary player a Coke and gets his jersey in return, became an instant classic – illustrating the emotive power of blending sports heroes with brand messaging. It was a precursor to the idea that Super Bowl ads could be as anticipated as the game, a notion cemented by Apple’s “1984” ad a few years later.

On the endorsement front, the 1970s saw deals grow larger and more numerous. Athletes like Pelé (global soccer and sports icon) and GOAT Muhammad Ali were sought by companies worldwide for endorsements, reflecting the globalization of sports fame. In the U.S., one of the most lucrative endorsement battles of the 70s was in sneakers: Puma and Adidas (run by rival Dassler brothers) and new challenger Nike competed for star athletes.

Nike, founded in 1964 as Blue Ribbon Sports by Phil Knight and Bill Bowerman was still small in the early 70s but marketed shrewdly. A watershed moment came when Nike signed distance runner Steve Prefontaine in 1973, one of its first athlete spokesmen, linking the brand with a rebellious, youthful image. By the end of the 70s, Nike’s bold marketing and innovative shoes were eroding Adidas’s dominance, showing how a challenger brand could use athlete endorsement (and emerging jogging/fitness trends) to gain market share.

Another technological and marketing innovation of this era was the advent of closed-circuit and pay-per-view sports events. The famous 1975 “Thrilla in Manila” Ali vs. Frazier boxing match was shown on closed-circuit screens in hundreds of locations, essentially an early pay-per-view model. Fans paid to watch live via satellite feed, an idea that would later turn into pay-per-view TV for boxing, wrestling, and eventually mainstream sports packages. This created a new revenue model for sports content beyond free TV – something that would explode with cable and satellite in the 80s and 90s.

Finally, the late 1970s brought a channel that changed sports marketing forever: ESPN, launched in 1979. With the slogan “All sports, all the time,” ESPN was the first 24-hour sports network. In its early years, it aired everything from Australian rules football to billiards to fill time, but it soon secured deals for college basketball, the NFL Draft, and more. Skeptics doubted if a full-day sports channel could survive, but by obtaining rights to broadcast major league games (NBA, NFL highlights, etc.) and with creative programming, ESPN grew rapidly.

For marketers, ESPN meant more inventory to advertise against sports – not just big games, but highlight shows, talk shows, and niche sports that still delivered target demographics. By the 1980s, ESPN would start to turn profits and become a must-buy for sports advertisers. The network also nurtured a new style of brash, personality-driven sports content (think SportsCenter catchphrases), further blurring the line between sports and entertainment.

Impact and Legacy: The 60s and 70s firmly established that sports were prime marketing real estate, worthy of big investments. The innovations of this era have direct lines to today: The global sponsorship frameworks built by Horst Dassler and others became the norm for Olympics, World Cups, and leagues (we see it in uniform sponsors, “official partner” programs, and huge naming rights deals worldwide).

Monday Night Football’s success paved the way for more weeknight and primetime games (e.g. NBA on TNT Thursdays) and showed leagues the value of TV scheduling and showmanship – something the NFL especially has maximized. Super Bowl advertising was on its way to becoming as famous as the game; indeed, Apple’s 1984 commercial (aired in Jan 1984) would soon redefine Super Bowl ads as cultural events.

By signing athletes to contracts unprecedented in length or value (like Dr. J or Magic Johnson and Larry Bird with Converse shoes, or Nadia Comăneci endorsing products after the ’76 Olympics), the 70s proved athletes could be global brand ambassadors. The rise of ESPN signaled that fans’ appetite for sports content was effectively limitless – a hint at the 24/7 sports news cycle and on-demand access we take for granted now. In summary, this era took the foundation built earlier and supercharged it: more viewers, more money, more creativity. Sports marketing was now entrenched as a key part of the sports industry and popular culture.

Timeline: Key 1960s–1970s Milestones

- 1960: Mark McCormack signs golfer Arnold Palmer and founds IMG – launching sports management and marketing as an industry. This professionalized athlete endorsements and broadcast deals through dedicated agents.

- 1964: Phil Knight and Bill Bowerman found Blue Ribbon Sports (later Nike). By 1984 Nike’s signing of Michael Jordan (see next era) will make it a dominant force, but the groundwork of Nike’s marketing-driven approach started now.

- 1967: First Super Bowl is held. The AFL-NFL Championship, as it was first called, becomes a marquee TV event almost immediately. A 30-second ad costs ~$40k; this will skyrocket in coming decades as Super Bowl Sunday becomes advertising’s biggest stage.

- 1970: Monday Night Football debuts on ABC (Sept 1970). The NFL in prime time draws huge audiences and ushers in a new era of sports-entertainment television. Advertisers reap the benefits of a consistent, massive national audience each week.

- 1975: “Thrilla in Manila” Ali vs. Frazier fight is broadcast via closed-circuit TV to paying audiences. Marks one of the first major pay-to-watch sports events, foreshadowing the pay-per-view model.

- 1976: Montreal Olympics struggle financially, but in their wake the IOC (with influence from Horst Dassler) devises a global sponsorship program to fund future Games. (By 1984, the Olympics will be a marketing success story – see next section.)

- 1979: ESPN launches as the first 24-hour sports network. The network provides a constant platform for sports advertising and revolutionizes sports media coverage.

- Late 1970s: Athlete endorsements hit new highs – e.g., tennis star Björn Borg’s Fila and Diadora deals, and NBA star Julius “Dr. J” Erving’s shoe deal – showing that celebrity athletes can define brand images in apparel, a trend that will explode with Air Jordan.

1980s–1990s: Globalization and the Boom Moment in Sports Marketing History

By the 1980s and 1990s, sports marketing had become a massive, global business. This era was characterized by the emergence of sports mega-events as media spectacles, the rise of athlete superstars whose endorsement deals reached unprecedented levels, and the global expansion of sports audiences through satellite TV and later the internet. Marketing campaigns around sports grew more sophisticated and big-budget, with brands treating sports premieres (like the Olympic Games, World Cup, or Super Bowl) as critical battlegrounds for consumer attention.

A defining moment in the 1980s was the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games, which demonstrated just how profitable sports marketing could be. Under the leadership of Peter Ueberroth, the LA Olympics were the first privately funded Olympics and aggressively pursued corporate sponsors, selling exclusive sponsorships in various categories. The result: a surplus of over $225–250 million – the first Olympic Games to turn a profit in decades (Sen, 2024).

Companies like Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, Kodak, and others paid millions to be official sponsors of LA 1984, and in return they received prime advertising spots and brand exposure to billions of viewers worldwide. This success changed the Olympics forever; it proved the viability of the sponsorship model on a grand scale, and the IOC formalized this with the TOP program in 1985, limiting the number of global sponsors (thus increasing exclusivity and prices). The 1984 Olympics are often cited as the point when the Olympic movement fully embraced corporate marketing, shaping today’s highly commercialized Games.

Ueberroth’s strategies (like category exclusivity and long-term partnerships) became standard practice in sports event marketing and influenced other leagues as well.

If one athlete defined sports marketing in the 1980s, it was Michael Jordan. When Nike signed the rookie Jordan in 1984 to an endorsement deal, they created the Air Jordan line of shoes the following year – and nothing was ever the same. The Air Jordan I sneaker (released 1985) was backed by an edgy marketing campaign (“banned” by the NBA for uniform violations, as Nike’s ads touted) and it sold out nationwide, launching the sneakerhead culture. Jordan’s charismatic on-court performances and Nike’s savvy marketing formed a perfect symbiosis. The partnership became one of the most iconic sports marketing collaborations in history (Collins, 2024).

Over the years, Nike and Jordan expanded the brand to apparel and dozens of shoe models, generating billions in revenue. Jordan’s success showed how a single athlete could transcend his sport to become a global brand. By the early ’90s, Michael Jordan was earning far more from endorsements (Nike, Gatorade’s “Be Like Mike” campaign, McDonald’s, etc.) than from his NBA salary – a blueprint for modern superstars. His $2.5 million per year Nike deal in 1984 (considered huge then) grew exponentially; by 1992 the Air Jordan franchise was so valuable that it helped Nike overtake all competitors in the athletic shoe market.

Jordan’s global fame, boosted by the 1992 Barcelona Olympic “Dream Team” appearance, demonstrated the power of using an athlete as the centerpiece of a brand’s identity. Sports marketing became personality-driven in a new way: companies wanted not just champions, but charismatic figures who could connect with consumers on a personal level.

Television and media rights deals hit new heights in this era. The NFL negotiated increasingly lucrative TV contracts – for example, in 1982 the NFL signed a $2.1 billion, 5-year package with the networks, a record at the time. By the 1990s, live sports broadcasts routinely drew some of the largest audiences in television, allowing networks to charge top dollar for ad time. The Super Bowl in particular became an advertising phenomenon. Apple’s famous “1984” Super Bowl commercial (introducing the Macintosh computer) aired in January 1984 and is widely cited as a turning point.

That cinematic, $900,000-budget ad (directed by Ridley Scott) stunned viewers and showed the creative potential of Super Bowl spots. After Apple’s “1984”, Super Bowl ads increasingly became big-budget, highly anticipated events in their own right.

Through the late ’80s and ’90s, advertisers competed to produce the most memorable Super Bowl commercials, from Budweiser’s Clydesdales to Cindy Crawford’s Pepsi ad. The cost of a 30-second Super Bowl spot crossed $1 million by the early 1990s (Su & McDowell, 2020).

By 1999 it was over $2 million, and climbing. This era firmly entrenched the Super Bowl as the premier showcase for advertisers – a trend that only grew (costs would exceed $5 million by 2017 and around $7 million by mid-2020s). The Super Bowl exemplified a broader trend of sports broadcasts as must-watch communal events – in an era of fragmenting media, live sports remained one of the few things everyone watched together, which marketers recognized as gold.

Meanwhile, international sports events expanded their marketing reach thanks to satellite and cable TV. The FIFA World Cup, for instance, gained a massive U.S. audience for the first time with the 1994 tournament held in the USA (which was heavily sponsored by brands like Mastercard, Snickers, and Philips). The World Cup and Olympics in the ’90s leveraged global TV audiences and attracted more multinational sponsors than ever. Formula 1 auto racing also globalized in this period, bringing on sponsors from new markets (e.g., tech companies started sponsoring F1 teams).

Sports apparel became everyday fashion: wearing NBA jerseys or soccer shirts became a statement, effectively turning fans into walking advertisements. The NBA’s global surge in the ’90s – powered by Jordan and the Dream Team – translated into merchandise sales worldwide, and sneaker marketing became a cultural force (Nike’s “Just Do It” campaign, launched in 1988, ran globally and associated everyday fitness with heroic athletic imagery).

Another key trend was the increased marketing of women’s sports and athletes in the late ’90s. In 1996, the WNBA (women’s basketball league) launched, backed by the NBA’s marketing machine. Stars like Mia Hamm (soccer) and the Williams sisters (tennis, who turned pro in the late ’90s) landed endorsement deals, reflecting a recognition that female athletes could inspire consumers as well. In 1999, the U.S. Women’s Soccer Team won the World Cup at home in a landmark moment: the final had 90,000 fans in attendance and millions watching on TV.

Sponsor Nike seized the moment by erecting a huge billboard in New York of Brandi Chastain (who famously celebrated by ripping off her jersey) with the slogan “Pressure Makes Us”. This indicated a shift – advertisers were now willing to build campaigns around female sports moments, an idea that has continued to grow.

By the end of the 1990s, technology was on the cusp of changing sports marketing yet again. Internet websites for teams and leagues started appearing, and though slow dial-up connections limited multimedia, some pioneering campaigns emerged (e.g., in 1999, Victoria’s Secret controversially aired a Super Bowl ad directing viewers to an online fashion show – one of the earliest examples of blending TV sports audiences with internet marketing). Sports leagues also began experimenting with online highlights and engaging fans via emerging web portals like AOL or Yahoo. This set the stage for the transformation of the 2000s.

Impact and Legacy: The 1980s–90s took sports marketing into the stratosphere. The financial boom from TV deals and sponsorships made sports into a major sector of the economy. Athlete endorsements became multi-million (even hundred-million) dollar enterprises – by 1996, Nike could sign a young Tiger Woods to a 5-year, $40 million deal straight out of college, a direct result of the path blazed by Jordan. The global nature of sports marketing became undeniable as events like the Olympics and World Cup commanded audiences on every continent, leading brands to plan campaigns with global appeal (e.g., Coca-Cola’s multilingual ads, Adidas signing players from many countries).

The creative bar for sports advertising was raised – especially during the Super Bowl – influencing advertising approaches across all industries (companies began teasing or releasing ads early to create buzz, a practice that started in late 90s and 2000s). By 2000, sports and marketing were so intertwined that fans almost expected big commercials and sponsorship activations as part of the sports experience.

This era also laid groundwork for embracing new media. The late 90s hint of internet usage would explode in the 2000s; meanwhile, cable TV brought niche sports to specific audiences (ESPN launched ESPN2, and regional sports networks flourished, carrying local teams with local ads). Sports merchandising became a key revenue stream for leagues – licensed jerseys, trading cards (which evolved into high-end collectibles), and video games (the Madden NFL game franchise turned the NFL into year-round interactive entertainment, further marketing the sport to youth). All these developments from the 80s and 90s created a robust sports marketing ecosystem that was primed to enter the digital age.

Timeline: Key 1980s–1990s Milestones

- 1980: Mitsubishi installs the first giant video replay board (forerunner of the Jumbotron) at Dodger Stadium. By mid-80s, Sony’s “Jumbotron” appears. These create new in-stadium ad inventory and transform the fan experience with sponsored replays and graphics.

- 1984: Apple’s “1984” Super Bowl commercial airs, becoming one of the most famous ads ever and elevating Super Bowl advertising into an art form. It’s later called a “turning point” after which Super Bowl ads grew in creativity, influence, and cost.

- 1984: Los Angeles Olympics – first privately funded Olympics – secure $126 million+ in sponsorships, resulting in a $232 million surplus. Proves the Olympic Games can be a profitable marketing venture, not a financial drain.

- 1984: Nike launches the Air Jordan line with Michael Jordan. The Air Jordan sneaker becomes an instant cultural icon, and Jordan’s persona drives Nike’s sales to new heights. Athlete branding reaches new potency.

- 1985: NBA approves shoe deals and endorsers more freely (after seeing the buzz from Air Jordan). The same year, the IOC begins The Olympic Partner (TOP) program to sell exclusive global sponsorships, institutionalizing the practices proven in ’84.

- 1988: Nike’s “Just Do It” campaign debuts, blending inspirational sports imagery with marketing in a way that resonates globally. Shows the emotional power of tying brands to athletic achievement and personal challenge.

- 1992: The USA Basketball “Dream Team” competes at Barcelona Olympics, essentially a marketing showcase for the NBA globally. Sponsors and apparel companies (like Reebok, who made the team’s uniforms, and Nike, who had most players signed) benefit enormously as NBA stars become international celebrities. The event turbocharges the NBA’s international growth and its merchandise sales overseas.

- 1994: FIFA World Cup in the USA sets attendance records and attracts major U.S. corporate sponsors, showing soccer’s marketing potential in America.

- 1996: Atlanta Olympics – Centennial Games – are saturated with sponsorship and branding, sometimes drawing criticism for over-commercialization, but also netting huge revenues for organizers and partners.

- 1996: Launch of the WNBA, backed by substantial marketing from the NBA and partners (like Nike and Spalding), marking a commitment to a professional women’s league with major sponsors.

- 1999: Women’s World Cup final in USA – 90,000 in attendance and an estimated 40 million U.S. TV viewers – becomes a landmark for women’s sports marketing, leading to increased endorsements for stars like Mia Hamm and Brandi Chastain. Nike’s marketing around the event hints at future campaigns centered on women athletes.

21st Century: The Digital Revolution and Social Media Era (2000s–Present)

Entering the 2000s, sports marketing underwent another revolutionary change with the advent of the internet, social media, and new digital technologies. The core principle – connecting brands with the passion of sports fans – remained, but the methods and scale expanded dramatically. In this era, marketers can reach fans instantly worldwide via digital channels, athletes can communicate directly to millions of followers, and data analytics allows more targeted and personalized marketing than ever before.

In the early 2000s, digital marketing in sports started with official league and team websites, email newsletters to fans, and online banner ads on sports news sites. Leagues like the NFL and NBA launched their own media platforms (NFL.com, NBA.com) to distribute news and highlights, often sponsored by advertising partners. A notable innovation was the rise of fantasy sports online – companies like Yahoo and ESPN ran fantasy leagues that kept fans engaged daily, and this opened new sponsorship opportunities (for example, a beer company sponsoring a fantasy football segment).

By the mid-2000s, sports marketers were also exploring SMS updates and mobile content, as cell phones became common. One early interactive campaign was in 2002, when Nike launched a web portal called Nikefootball.com with exclusive content around the World Cup, blending traditional advertising with online engagement – a sign of things to come.

However, the biggest game-changer was the explosion of social media in the late 2000s and 2010s. Platforms such as Facebook (2004), YouTube (2005), Twitter (2006), and Instagram (2010) profoundly transformed sports marketing. Suddenly, teams, leagues, and athletes had direct channels to communicate with fans in real time, unfiltered by journalists or TV networks.

This enabled what is now called athlete branding or influencer athletes – athletes cultivating their own image and fanbase on social platforms, often with guidance from their agents or sponsors. By sharing personal moments, training routines, or just opinions, athletes could grow huge followings. Brands quickly realized the opportunity: they started partnering with athletes not just to appear in TV ads or on cereal boxes, but to have them promote products on their social media accounts.

An athlete wearing a certain shoe in an Instagram post or doing a sponsored tweet about a car could instantly reach tens of millions of followers. In effect, top athletes became social media influencers on par with pop stars. As one marketing analysis put it, social media let athletes “cultivate their personal brands, offering glimpses into their lives…and monetising their influence through brand partnerships”.

For example, Cristiano Ronaldo – the most followed athlete on Instagram – can command hundreds of thousands of dollars for a single sponsored post, and he provides massive exposure for his sponsors through social media engagement.

This direct-to-fan communication has made sports marketing more continuous (not just around game time) and more personal.

Teams and leagues likewise leveraged social media for fan engagement and branding. Instead of relying solely on news coverage, every team now acts like a media company – posting highlights, behind-the-scenes videos, memes, and interactive content to keep fans hooked (and to serve sponsors). For instance, during big events like the Super Bowl or NCAA March Madness, teams and organizers use Twitter for real-time updates often tagged with sponsors (e.g., a “#SB51 Halftime Show presented by Pepsi” trending topic).

Social media “challenges” and hashtags have involved athletes and fans in co-creating marketing content – a notable example is the 2014 Ice Bucket Challenge, which, while for charity, saw many athletes participate and spread virally, demonstrating the network effect of social platforms. Brands love to latch onto these viral sports moments: when a power outage paused the 2013 Super Bowl, Oreo famously tweeted “You can still dunk in the dark,” a real-time marketing coup that was retweeted thousands of times, heralding the era of agile, reactive marketing around sports.

Moreover, digital technology has introduced new forms of sports advertising such as virtual signage. Broadcasters can now digitally overlay ads on the field or behind home plate that only TV/streaming audiences see (while in-person fans see something else). This means sponsors can target TV viewers with region-specific ads – for example, during international soccer broadcasts, a Chinese sponsor’s logo might appear on the pitch for the China audience and a different sponsor for European audiences.

The NBA has experimented with augmented reality (AR) apps that let fans point their phone at the court and see extra graphics or stats, often sponsored by a brand. And with data analytics, marketing has become smarter: teams analyze fan data from ticket purchases, social media, and mobile app usage to tailor promotions (like special offers for a fan’s birthday or personalized merchandise ads).

The rise of influencer marketing in sports extends beyond athletes to ordinary fans who became content creators. Platforms like YouTube and TikTok saw the emergence of sports commentators and trick-shot artists (think Dude Perfect) who amass huge followings and collaborate with sports brands. These influencers are sometimes invited by leagues to events or given sponsorship deals themselves, as they can reach younger demographics more effectively than traditional ads.

A major development in 2021 was the change in U.S. college sports rules allowing NCAA athletes to monetize their Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL). This meant suddenly even college athletes could do commercials, appear in local ads, or get paid for social media posts. A whole new frontier of sports marketing opened, with brands signing popular college quarterbacks, basketball stars like Caitlin Clark or Angel Reese, or even gymnasts and TikTok-famous athletes to endorsement deals. It is still evolving, but it reflects how the concept of “athlete-as-brand” has penetrated all levels of sports.

In summary, the 21st-century landscape is about constant engagement and global reach. A fan in India can follow the NBA or Premier League as closely on Twitter/YouTube as a local fan; a sportswear ad campaign can be launched simultaneously in dozens of countries via digital channels. The boundaries are gone. And everything is faster: marketing campaigns react in real time to sports moments, and fans respond instantly (for better or worse) on social media. Companies must be more nimble and creative – leveraging trends like memes or esports (another new arena; eSports competitions themselves attract sponsors and marketing similar to traditional sports).

At the same time, traditional pillars like the Super Bowl, Olympics, and World Cup remain incredibly important – in fact, even more so, as they anchor the fragmented viewing habits with huge live audiences. The Super Bowl continues to break records: a 30-second ad hit a record $8 million by 2025.

Brands now release teasers for their Super Bowl ads on social media to maximize impact. The Olympics and World Cup integrate social media campaigns with their sponsorships (e.g., Coca-Cola’s 2014 World Cup campaign included a Twitter hashtag and music video).

Impact and Legacy: The digital and social media era has made sports marketing more global, immediate, and interactive than ever. Brands now engage in two-way conversations with fans and often position themselves as part of the fan community (for example, Wendy’s fast-food chain running snarky Twitter commentary during March Madness to build rapport with young fans). Athlete-driven content has in some cases reduced the reliance on traditional commercials – fans might see their favorite player endorse a product on Instagram and find that more authentic than a TV ad. This era also sees data-driven marketing, where every click or view is measured – sponsors expect tangible ROI metrics like engagement rates, not just impressions.

Looking at long-term effects, many earlier innovations enabled today’s strategies. The celebrity athlete endorsementsthat started with Wheaties and Jordan are now supercharged by social media – but it’s the same principle of leveraging star power, just delivered in a tweet or TikTok. The corporate sponsorship frameworks developed in the 70s and 80s continue, now extended to digital assets (like sponsors for a team’s mobile app or esports team).

The fan loyalty cultivated over decades still underpins everything: fans are fiercely loyal to their teams and favorite players, and sports marketers continue to find creative ways to tap into that devotion, whether via a throwback jersey campaign that evokes nostalgia or an augmented reality photo-op at the stadium that fans will share online.

As we move forward, sports marketing shows no sign of slowing. If anything, new technologies like virtual reality could offer immersive branded experiences, and data analytics will further personalize marketing (perhaps every fan in a stadium could see a personalized ad on their phone during halftime based on their interests). But amidst the change, the essence remains: sports stir passion, and where there is passion, there is an opportunity for marketing – connecting brands to consumers through the joy, drama, and community of sports.

Timeline: Key 21st-Century Milestones

- 2000: The NFL launches NFL.com and sells streaming audio subscriptions for games – early steps into online direct-to-consumer content. Brands begin placing banner ads on league websites, marking the start of internet sports advertising.

- 2005: Launch of YouTube – by 2006, clips of sports highlights and memorable moments circulate widely (often pirated at first). Recognizing the demand, leagues eventually create official YouTube channels (NBA in 2005, NHL 2006) to share highlights with ad support, shifting how fans consume (and how sponsors can present) highlights.

- 2006–2010: Social media era begins. Teams and leagues join Facebook and Twitter en masse. Athletes like Shaquille O’Neal (early on Twitter) and Lance Armstrong (early on Twitter) use these platforms to connect with fans, opening new marketing channels.

- 2010: Old Spice launches its “The Man Your Man Could Smell Like” ad during the Super Bowl and extends it with a viral YouTube and social media campaign featuring interactions with athletes – a case study in blending traditional and digital sports marketing.

- 2013: Oreo’s “dunk in the dark” tweet during the Super Bowl blackout goes viral, highlighting the rise of real-time marketing around live sports events.

- 2014: The FIFA World Cup in Brazil becomes the most-tweeted event in history up to that point; sponsors run integrated social media campaigns (e.g., Adidas’s #allin hashtag). Demonstrates the global second-screenexperience – fans discussing the event online – which advertisers actively join.

- 2016: The NBA becomes the first major US league to allow corporate sponsor patches on team jerseys. This echoes the tradition in international soccer and opens another visible branding spot (by 2023, most NBA teams have a jersey sponsor, worth $5–20M per year).

- 2016: Pokémon Go craze sees some sports venues using the AR game to lure fans to stadiums (with sponsored “Pokéstops”), an early crossover of AR gaming and sports marketing.

- 2018: The Supreme Court ruling in the US allows states to legalize sports betting. Soon, betting companies become huge sports sponsors and advertisers, integrating betting odds into broadcasts and promotions. This created a new category of sports advertiser (DraftKings, FanDuel, etc.) spending heavily on marketing to sports audiences.

- 2020: The COVID-19 pandemic forces sports behind closed doors. Marketers adapt with virtual fans and signage– e.g., the NBA’s “bubble” games feature digital screens with fans on Zoom (sponsored by Michelob Ultra). Without in-person attendance, digital engagement skyrockets, and sponsors pivot to online activations.

- 2021: NCAA’s NIL rule change allows college athletes to sign endorsement deals. Within months, top college athletes, gymnasts, and others ink partnerships with brands and start monetizing social followings – the birth of a new facet of sports marketing.

- 2022: Beijing Winter Olympics and Qatar World Cup both feature extensive social media content and controversy-driven engagement (sponsors have to navigate political issues more than ever). Meanwhile, cryptocurrency companies invest in sports marketing heavily (Crypto.com renames LA’s Staples Center; FTX sponsors esports and MLB umpires) – though this trend cools by 2023 with the crypto downturn.

- Present: Athletes like LeBron James, Roger Federer, Serena Williams end their careers with lifetime endorsement earnings in the hundreds of millions, much of it driven by global social media exposure. Teams launch their own NFTs and digital collectibles to engage young fans in new ways. Sports marketing continues to innovate with technology – but always with the goal of capturing the excitement of sports and the loyalty of fans.

Conclusion: How Sports Marketing Changed the Sports Industry and Sports Ecosystem

In conclusion, from the tobacco cards of the 1870s to the Twitter and TikTok campaigns of today, the history of sports marketing is a story of continual innovation. Each era built on the last: early print ads and athlete cards fed into the endorsement culture of the 20th century; the advent of radio and TV multiplied audiences, turning sports into big business; creative sponsorships and superstar branding in the late 20th century set the stage for the globally interconnected, digital-savvy sports marketing universe we navigate now.

Sports marketing has not only mirrored changes in technology and society, it often has led the way in inventing new marketing techniques. And as long as sports captivate human hearts, marketers will continue finding fresh ways to join the game – connecting brands with the thrill of victory, the agony of defeat, and the enduring passion of the fans.

CITATION

Bakanauskas, P. (2025, March 4). Sports Marketing History 101: Legendary Game-Changing Moments That Shaped the Sports Industry. Play of Values. https://playofvalues.com/sports-marketing-history/

IN-TEXT CITATION: (Bakanauskas, 2025)

List of References

- Biography: Mildred “Babe” Didrikson Zaharias. (n.d.). National Women’s History Museum. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/mildred-zaharias

- Collins, M. (2024, September 28). A history of sports and Advertising – Mob film. Mob Film. Link.

- Heffernan, C. (2023a, October 11). Guest post: The Detailed History of Sports Marketing and Advertising – Physical Culture Study. Physical Culture Study – A Website Dedicated to the Study of Strength, Health, Fitness and Sport Across Centuries, Countries and Contests. Link.

- Kindy, D. (2021, July 27). How Wheaties became the ‘Breakfast of Champions.’https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/how-wheaties-became-breakfast-champions-180978246/

- Moritz, B. (2017, May 10). The history of sports journalism (Part 1 of 3). Sports Media Guy. Link.

- Sen, B. (2024, December). THE 1984 LOS ANGELES OLYMPICS AND THE COMMERCIALIZATION OF THE GAMES. Gamers. Link.

- Sports Business Journal. (2005, December 26). An end of an era: The impact of ABC’s “Monday Night Football.” Sports Business Journal. Link.

- Su, R., & McDowell, E. (2020, February 2). How Super Bowl ad costs have skyrocketed over the years. Business Insider. Link.

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (1998, July 20). Don Carter | Biography, Bowling, & Facts. Encyclopedia Britannica. Link.

- The McCormack Legacy : Isenberg School of Management : UMASS Amherst. (n.d.). Link.

- Thorn, J. (2018, May 1). The changes wrought by the great base ball match of 1858. Medium. Link.